A M D G

BEAUMONT UNION REVIEW

WINTER 2025

In 1876, Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India and Custer made his 'last Stand' at the Little Bighorn, it was also the year that the Beaumont Union was founded. The idea was mooted after the Shrovetide play put on by some old boys, by Charles Roskell (the first pupil) chatting with the Rector Fr Welsby in the Second Guest room. Why the Second rather than the First is open to speculation, but the result was that in April a letter went out to all and sundry by a committee formed under Roskell, now a solicitor, with William Munster (MP for Mallow), Robert Berkeley (Master of the Berkeley Hounds and High Sherriff of Worcestershire), Frederick Barff ( Barrister) and Bernard Parker (Solicitor and son of the Premier of New South Wales). A fairly eclectic bunch with lawyers predominating as they always have in the B U. They had about 60 positive replies and on 1st November the Society was launched with two other committee members Charles Clifford (Country gentleman and Squire) and Charles Pedley (father won the 1847 Derby). The first Dinner was held at the Criterion the following year with the Hon Charles Russell in the Chair. He in fact deputised at the last moment for Joseph Monteith ( Land owner in Lanarkshire) and as a boy " his reckless behaviour riding across Runnymede had caused an old gentleman to fall from his horse into a ditch". He sounded an admirable though probably unwise choice. Now 150 years on I very much hope that I can rely on as many as possible to join us in May at Beaumont to celebrate what may be a last "Hurrah" and what we believe has been a force for good and friendship over the years.

In 1876, Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India and Custer made his 'last Stand' at the Little Bighorn, it was also the year that the Beaumont Union was founded. The idea was mooted after the Shrovetide play put on by some old boys, by Charles Roskell (the first pupil) chatting with the Rector Fr Welsby in the Second Guest room. Why the Second rather than the First is open to speculation, but the result was that in April a letter went out to all and sundry by a committee formed under Roskell, now a solicitor, with William Munster (MP for Mallow), Robert Berkeley (Master of the Berkeley Hounds and High Sherriff of Worcestershire), Frederick Barff ( Barrister) and Bernard Parker (Solicitor and son of the Premier of New South Wales). A fairly eclectic bunch with lawyers predominating as they always have in the B U. They had about 60 positive replies and on 1st November the Society was launched with two other committee members Charles Clifford (Country gentleman and Squire) and Charles Pedley (father won the 1847 Derby). The first Dinner was held at the Criterion the following year with the Hon Charles Russell in the Chair. He in fact deputised at the last moment for Joseph Monteith ( Land owner in Lanarkshire) and as a boy " his reckless behaviour riding across Runnymede had caused an old gentleman to fall from his horse into a ditch". He sounded an admirable though probably unwise choice. Now 150 years on I very much hope that I can rely on as many as possible to join us in May at Beaumont to celebrate what may be a last "Hurrah" and what we believe has been a force for good and friendship over the years.

EDITOR Further note:

This was supposed to be the Christmas Edition but it was held up, partially because I have been busy on other writing ( see further below), and have spent a lot of time abroad in the last few months and then we were into the Christmas / New Year break for the 'Website Manager'.

I trust you will take this as 'reasons' rather than 'excuses'.

A belated Happy Christmas and New Year to one and all.

NEWS

THE B U 150th ANNIVERSARY PARTY

The Party will take place at Beaumont on Friday 22nd May. The full programme will be confirmed in due course but will include:

Mass celebrated by Bishop Jim Curry. ( hopefully in the Chapel)

Champagne Reception on the Captain's Lawns.

Luncheon.

Members with their Wives, Girlfriends, "Partners" are invited.

Cost will be kept to under 100 per head.

Details to follow but in the meantime PLEASE put the date in the Diary. This will probably be our last major gathering.

STATE OF THE UNION.

We have 292 members of whom some 50 regularly attend events. Others through distance, infirmity and age remain with us in spirit and keep in touch. There are a good many though that during my time 'at the helm' (ten years +) I have never heard from but I trust still enjoy getting these missives.

THE LUNCH

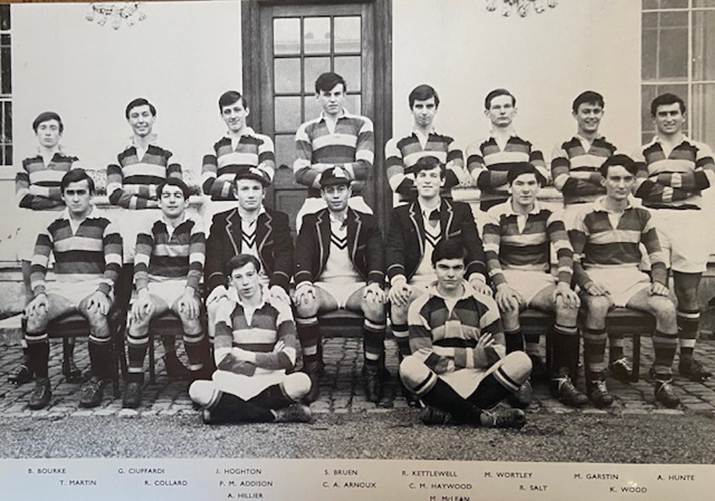

Forty members were at The Caledonian for our annual lunch: the following attended.

Romain de Cock (Chairman),John Flood, Michael Wortley, Chris Newling- Ward, Michael Newton, Peter Savundra, Patrick Solomon. Jeremy Gompertz, John Wolff, Nickolas Warren, Gerard de Lisle, Ant Stevens, Philip Critchley, Tim FitzGerald O'Connor, Robert Wilkinson. Ed Monaghan, Michael Morris, Oliver Hawkins Bishop Jim Curry, Amanda Bedford, Tony Outred, Derek Hollamby , Jonathan Coleman, Nigel Courtney, Stephen Crompton, Patrick Burgess, Richard Sheehan, Bertie de Lisle, Rupert Lescher, Chris Tailby, Julian Langham, Christopher McHugh, Richard McHugh ( Guest),Jonathan Johnson, Anthony Northey Michael Burgess, Edwin de Lisle, Varyl Chamberlain, Paul Dutton.

We all thoroughly enjoyed ourselves and Romain gave an excellent and often hilarious speech.

The Lunch has not "died a death yet!"

Rogues Gallery:-

The Chairman

Squire Gerard de Lisle Jeremy Gompertz Ant Stevens

John Wolff Philip Critcheley Edwin de Lisle Michael Burgess

Patrick Solomon Chris Newling-Ward Michael Newton

Michael Morris Ed Monaghan Jonathan Coleman

Mandy Bedford Tony Outred Oliver Hawkins

Anthony Northey Jonathan Johnson Chris McHugh

John Flood Peter Savundra Michael Wortley

Richard Sheehan Julian Langham Varyl Chamberlain

Stephen Crompton Chris Tailby Nigel Courtney

Bertie de Lisle Patrick Burgess

Derek Hollamby Bishop Jim

Tim FitzGerald O'Connor (it was an excellent Lunch)

REMEMBRANCE SUNDAY

Some 30 OBs attended the Mass together with wives and friends. We were fortunate to have Fr. Simon Hall celebrate for us. ( a onetime pupil of Simon Potter at Wimbledon College). Since the sale of St Johns last year there is no longer a Jesuit we can call upon for the day. It is a problem we will have to face for future years, especially with the shortage of priests.

Some of us were able to enjoy coffee, croissants, cakes and biscuits beforehand at St Johns where Philip Barr, his Staff and the boys made us all most welcome. Following the Mass, we had an excellent buffet lunch provided by De Vere in the old Lower line Refectory: as usual they looked after us exceedingly well. Let us hope that our tradition of Remembrance will continue for future years.

11th November

I took the Wreath from the previous year out to the Normandy Memorial at Ver- sur - Mer and laid it there on your behalf.

THE DERMOT GOGARTY MASS.

22 November at St Johns

John Flood writes:

The Dermot Gogarty Memorial Mass, the day after his 20th anniversary, was mainly attended by the family and a few friends. I told Kathy we were privileged to be invited there and represent both his Memorial Trust trustees and the Beaumont Union

His brother (2 years older) spoke very well, including of the importance Dermot had expressed for the family sticking together, and paid tribute to his and Kathy's children, spouses and the grandchildren. He also revealed what Dermot would probably have looked like at the age of 68 as the two brothers had been so alike in their forties. A best friend of Dermot from their South Africa days spoke first and was full of praise for him. Kathy also spoke briefly to thank everyone for being there. All their 5 children and 9 grandchildren were there, I would envisage the eldest grandchild being 9 or 10.

Fr Dermot Power, former chaplain to both SJB and St Mary's Ascot, celebrated the Mass, mostly from a seated position, in a warm and very meaningful manner, including his own tribute to Dermot as the introduction, from which it was apparent how special he felt it was to be celebrating Mass again in the SJB Chapel. In an effort to make the Mass more meaningful for the grandchildren he inserted a shortened version of the hymn 'Sing Hosanna', instead of the Sanctus, and later included a verse of 'He holds the whole world in His hands', as well as including the Taize Hymn 'Jesus remember me when I come into Your Kingdom' at Communion, having practised all of these with the children before the Mass started.

It was poignant to see the current headmaster, Philip Barr, sitting in the seat where Dermot used to sit, and later in the Mass assisting Fr Dermot as his server and Eucharistic Minister. It was especially delightful to see Dermot & Kathy's son and 4 daughters, twenty years on from when they were schoolchildren, with so many in the next generation, three of whom read the bidding prayers.

A truly extra special and very personal Mass to witness, celebrated by Fr Dermot in an exceptionally inclusive way, so well suited to the congregation of a remarkable family man and headmaster, whose earthly life ended so abruptly and tragically early but, as his best friend Matthew said, "Lives on".

OBITUARIES

I must inform you of the following deaths: may they rest in peace.

William Henry (52). A great supporter of the BU, a regular to Lourdes with the BOFS and especially remembered for his lunches given at Tandridge Golf Club for his contemporaries, players and no-players alike.

Sir Roger Clifford Bt (54). The last of the Cliffords and was at Beaumont with his younger twin brother Charles. He succeeded his Uncle Fr Lewis Clifford SJ (OB) and Rector in 1982 and lived in New Zealand. He was a 'cattle dealer' and racehorse owner. He was married with two daughters resulting in the Baronetcy being now defunct.

Roger Darby (62). He came to the school from Penryhn and joined the 'A' stream and was one of those that provided the backbone to the school. He played 3rd XV and 2nd XV, rowed 3rdVIII and 2nd VIII, rose to high rank in the Corps and was a member of virtually every society on offer. He appeared in every play going usually the parson or a person of gravitas and was a natural pairing with Michael "Binge' Tussaud in the Panto. Much to our disgust he was promoted to Monitor and left our dissident dining table half way through our final year. Roger didn't go to University : the days when Oxbridge or TCD and possibly Imperial were the only ones acceptable to the Js and started life in the Bank of England and gained a commission in the H A C. Roger put on a few pounds over the years and was content to be described as portly and I was not surprised that he had become a resident of Tunbridge Wells: it seemed appropriate to his character! A faithful supporter of the BU, he will be much missed at our gatherings.

NEW BOOK pending

I am currently finishing a new book with the 'Beaumont' connections to the world of racing: there were a good number including winners of all the Classics including the Derby and winners of the Grand National and other important 'jump' races.

"Threads of Racing Silk" covers owners, breeders, jockeys and the all -important horses up to the present day to include Coolmore the greatest 'powerhouse' in the sport. It should be published in the spring in time for the

B U Party in May.

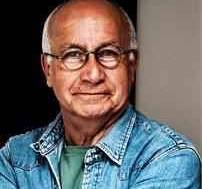

Lester Piggott , one of the greatest jockeys of all time in the colours of both Freddie and then John Wolff. He looks disgruntled and well he might be having just been 'dropped' in the paddock at Sandown. When Lester was at the centre of the largest tax evasion scandal of all time his defence barrister was an OB.

There are plenty more revelations between the covers.

ARTICLES

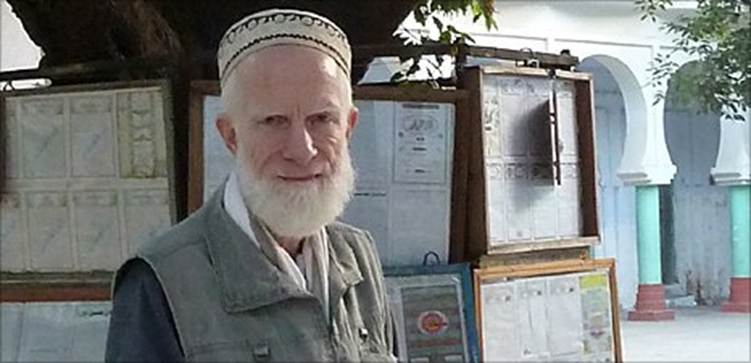

Beaumont's own IMAM

Last September John Butt (66) contacted me and in the course of an Email conversation I soon realised that he was not the 'usual' OB and has so far lived a fascinating life. To begin with he followed his father and two Uncles and his brother Richard to Beaumont. ( Richard now lives in The States but is not in contact with the BU). John's family were from Trinidad where his father Eric and his brother were all lawyers and Malcolm was the British Consul. John was one of those that had to go to Stonyhurst for 'A' levels; he didn't enjoy his time there and on leaving "went walkabout".

Initially John offered me an article on the BBC World Service where he had worked for a time and initially he sent me the piece you will find below. However, being the 'digger and delver' that I am, I found out more about our own Imam.

Credit: Leslie Knott of Tiger Nest Films.

AMDG

بسمه تعالى

From Beaumont to the BBC: my time in "uninstitutional institutions"

By John Butt (66)

The late Queen Elizabeth's visit to Beaumont, for the school's centenary in 1961, took place before my time at Beaumont. My elder brother Richard was there. I have it on his authority, and I believe it is documented elsewhere, that the monarch summed up her impressions of Beaumont with the memorable phrase, ". the most uninstitutional institution I have ever visited."

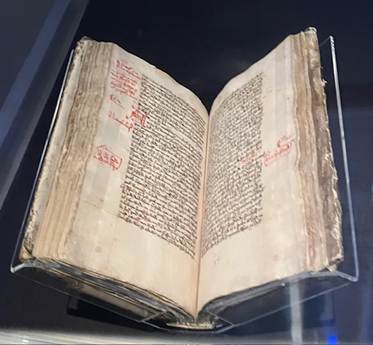

It must have been partly because the Beaumont spirit had rubbed off on me that, in 1990, I joined what at the time wasto my mindanother "uninstitutional institution"the BBC. If the Corporation had not been uninstitutional and uncorporational, one would find it difficult to imagine how they might have employed me. First of all, between my leaving school in 1968, and returning to England at the end of the 1980s, I had a series of escapades and adventures, mainly in Afghanistan. At the same time, I set about receiving a second education, in Islamic madrasas or seminaries, in the process learning several languages of Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. You could say that it was an Arabic/Persian version of the Latin/Greek classical education that the Jesuits were so adept at imparting. I graduated in 1983 from the "Oxbridge" of Islamic Studies in South Asia, Darul Uloom Deoband in north India, the only person of European origin ever to have done so. My Islamic education was the basis for me taking up a career in journalism. I had become leader-page editor for a Pakistani newspaper based in Peshawar when I decided to return to England in 1989, hopefully to advance my journalistic career there.

Of course, with a C.V like that, no one was faintly interested in what I had to offer. Except, that is, for the BBC. I applied for a job working on a South Asia daily current affairs programme. "You are lacking in the necessary broadcasting skills," the BBC Eastern Service wrote back to me, "but do get in touch and we will see how we can utilise your considerable experience of South Asia." Soon I was recruited for the BBC Pashto service, broadcasting to Afghanistan. The BBC, for their part, did not waste time in sending me back to Afghanistan.

The BBC had come up with an idea that only an uninstitutional institution like the BBC could come up with: a radio soap opera, modelled on the BBC Radio 4 radio drama series The Archers which, like The Archers, would help with what everyone hoped at the time would be post-war reconstruction in Afghanistan. The idea seemed eccentric to everyone outside the BBC. "The BBC is starting an Archers for Afghanistan," the Times diary at the time mentioned, in bemused and quizzical tone, as if to say, "What on earth is the BBC up to?" What was even more outlandish on the part of the BBC was that they thought Iwithout an iota of drama experience but knowing Afghanistan pretty wellwould be a good person to head what came to be known as BBC AEDthe Afghanistan Education Drama.

Inside the BBC, people thought differently. "He has the best job in Bush House," Bush House being where BBC World Service was based at the time, the head of training said of me, when I joined a Training of Trainers course for people about to undertake new assignments. "You have it worked out, don't you?" my fellow trainees said, when I gave them a summary of how I would go about my task as Editor of the Archers for Afghanistan.

Well, as it happened it did go pretty well. Our Archers for Afghanistan achieved 70 per cent steady listenership among Afghans based in Afghanistan, and those who were refugees in neighbouring Pakistan. We found numerous instances of the hold our Afghan Archers had on the imagination of listeners. One such example occurred when one of our characters had to be killed off, since the actor playing the part was emigrating to Australia. The character was so popular that prayer meetings were held in Afghanistan and neighbouring Pakistan for this totally fictional character.

It was not only the populace who were hooked. The Taliban, who were ruling Afghanistan at the time, exhonerated our audience research team from their ban on women's employment. We once ran a storyline, emphasising the need for women to be working in health centres. The storyline created such alarm among the Taliban that, when they found out that our audience research teamheaded by a womanwas passing by a provincial hospital, the Taliban authorities accosted them and said, "How come you are running storylines suggesting that we don't allow women to work in health centres? Please come inside and see how many women are working here." The storyline had not even mentioned Taliban, but they had taken it personally. That was the kind of impression the Afghan Archers exerted on all categories of Afghan society.

Which is where we return to our late monarch, and her penchant for the uninstitutional and unconventional. In my capacity as head of a pretty large BBC office based in Peshawar, I was invited to a reception for the Queen and Prince Philip, when they visited Pakistan in 1997. The reception took place on the lawns of the residence of the British High Commissioner in Islamabad. Everyone was organised in U-shape lines, so that the royal couple could easily pass by and greet everyone. I was dressed pretty smartly in a suit, but I did give myself away a bit with my Uzbek duppa or cap and longish beard. Her Majesty was intrigued enough to stop in front of me: "Where do you LIVE?" she asked. "I live in Peshawar, ma'am," I replied, feeling immediately at ease. "What do you DO there?" Her questions were penetrating, cutting to the core. I fumbled for a phrase or two, looking for words that would capture a monarch's imagination: "It's like an Archers for Afghanistan, if you can imagine that ma'am," was what came bursting out. "No, I can't imagine that. TELL me about it." She was clearly enthused and as I explained to her that we were constructing drama storylines that would help Afghans improve their lives, she kept nodding as if to say, "Yes, I understand, I get it." Her parting words were, "I think that's FANTASTIC," leaving me pretty chuffed and others in attendance maybe a bit jealous. But all the credit went to the work I was lucky enough to be doing, and the Queen's ability to see its value, in an instant.

In 2013, BBC World Servicealong with several parts of the BBCmoved from Bush House to New Broadcasting House. There is a clip available on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=se_5HC8SUBU showing Her Majesty's official opening of the new building. BBC World was on air at the time of her visit. Standing behind the glass panel that separates the newsreaders from the rest of the newsroom, she was shown on live television, followed by a horde of BBC journalists, while the presenters turned round and respectfully paid obeisance to the monarch. It was described as "one of the most bizarre pieces of live television you will ever see." It was an extraordinary piece of television engineered entirely by the Queen. One of the presenters at the time was Julian Warwicker of BBC World Service. "Everyone had been asked to stay in their places," he said of the "gaggle of people" who accompanied the Queen, "but as you know, in this building, if you are asked to do something, we tend to do exactly the opposite."

He was talking, of course, about the BBC, but he could just as easily have been talking about Beaumont.

Ed: I commented to John about his using AMDG at the top of the article and we both agreed that although a Jesuit motto, it was also most applicable to the Islamic faith as well.

THE HIPPIE WHO BECAME AN IMAM

By Nadene Ghouri

Forty years after following the hippie trail to South Asia, John Butt is still living in the region, and still spreading a message of peace and love - though now as an Islamic scholar.

As our car turned around the bumpy Indian road, a gleaming white marble minaret came into view. My fellow passenger, John Mohammed Butt, could barely contain his excitement.

"Can you see it?" he asks. "It's like the Oxford University of Islamic learning. For me these minarets and domes are just like the spires and towers of Oxford.

|

John Butt is the only Westerner to have graduated from Darul-Uloom Deoband |

"It's been almost 30 years since I was last here and I am still getting the same thrill. This is my alma mater."

The alma mater in question is Darul-Uloom Deoband, South Asia's largest madrassa, or Islamic school.

Driving through the madrassa gates, we entered a world rarely seen by Western eyes.

Deoband was built in 1866 by Indian Muslims opposed to the then British rule. Little has changed since - winding streets and tiny courtyards lined with stalls selling fragrant chai, bubbling pots of rice and paintings of Mecca.

Everywhere are the Talibs, religious students, young men with dark-eyed fervent expressions carrying books or quietly reciting the Koran.

And in another scene reminiscent of Oxford, students riding bicycles.

A chai seller recognises John and runs towards him. "John Sahib, John Sahib."

The two had not seen each other in decades, yet the man remembers him instantly. "John Sahib was the only student I ever saw who used to go jogging.

"There was only one John Mohammed - unique," he laughs.

That is perhaps not so surprising, when you learn that John Butt remains the first and only Western man ever to have graduated from Deoband.

He showed me his old dormitory room, a windowless cell where he spent eight years in a life of virtual seclusion, living under a regime of prayer and Koranic study.

But that is just one facet of this man's extraordinary life.

Aside from his time at Deoband, he has spent most of the past 40 years living among the fierce Pashtun tribes, who inhabit the lawless hinterland between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

He went there in 1969, he says, as a dope-smoking young hippie and never came home.

He laughs. "When people call me an ageing ex-hippie, I always reply that I am ageing maybe, but I'm certainly not ex. I'm still a hippie."

John Butt cuts an imposing figure.

At 6ft 5ins tall, he sports a long white beard and alabaster skin that is almost translucent.

Dressed in flowing white ethnic robes, he reminds me of a Benedictine hermit monk or a Victorian explorer, swashbuckling straight out of the pages of an historical novel.

He tells me he adores the Queen, Stilton is his favourite cheese and that football is his passion.

Yet among the border tribes, he is regarded as a native Pashtun and revered as an Islamic scholar. Home for him, until recently, was a tiny village in Pakistan's Swat valley.

Swat was once a popular tourist destination but is now the scene of regular battles between the Pakistani military and the Taliban.

But back in 1969, the young John was hooked from the moment he saw Swat, describing to me snow-capped mountains, rivers like flowing jewels, forests and alpine pastures.

It was, he says, "like Tolkien's Middle-earth, magical and other worldly" inhabited by tribal people who were "very pleasant, big-hearted, tolerant, easy-going and welcoming".

When his fellow hippies grew up and went home to become accountants and lawyers, John stayed on - becoming fluent in the Pashto language and studying Islam.

But John's world changed in the late 1980s, with the arrival of jihadists, who came to the border areas from all over the world to fight the war against the Russians in Afghanistan.

"I saw the rural, religious Pashtun way of life I had come to love so much being diluted, contaminated and poisoned, in particular by Arabs from the Middle East," he says.

"The way they practise Islam is very different to the tribal areas, but they used money and influence to impose their own set of values."

So he decided to fight for his adopted culture.

Peaceful Islam

In the early 1990s, he joined the BBC World Service Pashto service and helped to set up New Home New Life, a now iconic Afghan radio soap opera, known as The Archers of Afghanistan.

Six years ago, he set up a radio station which broadcasts across the Afghan-Pakistan border and which tries to promote tribal traditions along with peace and reconciliation.

|

|

More recently, John has switched his attentions back to Afghanistan and is spearheading the formation of a new Islamic university in the predominantly Pashtun city of Jalalabad.

"It makes perfect sense. There is currently nowhere in Afghanistan where a young man can do higher Islamic studies. They go to Pakistan, where as we know some of them have become radicalised," he says, emphasising that his university will give a platform to moderates.

But this promotion of peaceful Islam has set him on a collision course with militants. His beloved Pakistan has now become too unsafe for him.

"Swat is a militarised zone and people I see as foreigners there now treat me like I'm the foreigner, even though I lived there for 40 years.

"It's hard to work out who is who any more - who is Taliban, who is criminal. The waters are very muddy."

Last year, waters of another kind finally put paid to his idyll, when his house was washed away in the floods which devastated the area and killed thousands.

"It was a relief in some ways. When I lost the house, I knew I'd never go back there."

Afghanistan has also become increasingly perilous after Taliban death threats.

The Taliban have delivered so-called night letters - notes hand-delivered in secret and at night for maximum impact - warning students not to study at the university and denouncing John as a Christian missionary or an "orientalist".

Death threats have also been made to his teachers and staff.

"I've hired some of the best Islamic scholars in the region - pious, good and brave men," he says. "They know this is for the benefit of Afghanistan and they insist they will stay working with me despite the dangers."

As I said goodbye, he was planning to travel to Jalalabad on the local bus. We talked about the possibility of him being attacked and he admitted he could easily be killed.

But when I asked if he was scared, he brushed me off with a shrug. "You only die once. I could get hit by a bus tomorrow."

CHAMBERLAIN MEMOIRE

Guy (61) writes;

Before my father died in 1999 I asked him to write about his early life. He wrote it in three parts "His early Life and School at Beaumont ", he was Beaumont Captain, i think in 1936. "Preparation for War" and Finally "The War; Dunkirk". Then he died before recounting the remainder of the war!!

You review a lot of people and their war years and I wonder if you would like to see these pages, surely you would have to edit them. The remarkable thing is my father never had a diary or a computer yet almost 60 years later he can recall the dates, times places with extreme accuracy. There is a 2nd Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment web site and others have recorded identical events, exactly in keeping with my father's memory. I find this extraordinary, those times must have been extraordinary to have such detail imprinted on one's memory for 60 years.

My grandmother was a fervent Catholic, my grandfather, just a Christian, however he respected his marriage vows and sent my father to Beaumont.

My father's name is Maxwell Anthony Chamberlain but he was always known as Tony.

My mother is Frankie as in the attachment.

Maxwell as Captain of Boxing 1936

"My Life" - M.A. Chamberlain

My elder son Guy has persuaded me to jot down a few reminiscences, so starting with our family.

Volume 1 My early life and school years.

Unfortunately, I have no knowledge of my grandfather, Benjamin, on my father's side, from records he was born in 1851 and died in 1922 aged 71 years. He married Annie Georgina who was born 1861 and died in 1940 aged 79 years. My grandfather was a fairly wealthy man having an income of 3,000 per annum, until in 1902 a relation lost him his fortune and they had to move from a comfortable house in Dorking to a small house in Tulse Hill. He was, I understand, involved in the Brewing business and transportation. The financial loss meant that my father had to leave Eastbourne College and go to Hurstpierpoint College. I do not recall having ever met my grandfather however as I was 5 years old at the time of his death I must have done so. My grandmother I met regularly as I used to accompany my father who visited his mother every Tuesday without fail; she was a kind lady but rather regal and severe.

On the other hand my mother's father I knew well from the age of 3 years; his wife, my grandmother, died before I was born. Grandfather Searle was financially independent and lived at 'Blackmoor' at Kidmore a few miles from Reading. The property included a large farm run by Sid Cox and his wife, great friends of mine. Grandfather's two sons Percy and Gerald never attended school but were educated by tutors. He eventually lost his money which was all invested in Railways and came to live with us at 'Pendennis' in Sutton. He died around 1927 having been 3 years with us and was senile and slightly dotty. He used to steal candles and light them in his room!!! Very dangerous. A very kind and generous man, he would take me with him around the farm and we always visited 'Prince' and 'Fleur' two enormous carthorses and when in a good mood used to tip me a guinea a lot of money in those days.

I cannot recall any stories as my contact with both my grandparents was formal and not loving.

Sid Cox I remember far better; a real farmer figure, red of face, chewed straw and wore trousers with string around the knees and with a thick leather belt at the waist. He took me rabbiting with the ferrets, shooting, hay-making and advised me how to look after and tend some of the many animals and pets on the farm. His wife a large jolly woman, always at work in the large red-bricked cottage kitchen, fed me incessantly as she was convinced I never got a square meal at the big house.

I now come to my father, another Benjamin Thomas born 1886 died of Angina and Diabetics in 1966 aged 80 years. I know nothing about his school days other than that he was at Eastbourne College and Hurstpierpoint. A brilliant scholar and excellent sportsman excelling at gymnastics, hockey and fives and also holding the long-jump record at Eastbourne College for many years. On leaving school he took the Chartered Surveyor's Institute examination and passed out first. He was elected a Fellow of the Chartered Surveyor's Institution.

He joined the Civil Service and entered the Valuation Department of the Inland Revenue working at Somerset House and later at Bush House in the Strand. In 1937 he was awarded the Coronation Medal; he headed his Department and on Retirement became a consultant for Savills' a leading London Estate Agent.

He was an excellent Tennis player and first-class hockey player. He belonged to the Tulse Hill Hockey Club about the best in the South of England and earned his first Southern Counties Cap at the Midlands v South of England on 28th February 1914. Subsequently he earned his Cap for England and played for his country a number of times. (Cuttings from various newspapers are in an envelope in the file named 'family honours and awards' in the left hand bottom draw of my desk.) When he became too old for first class hockey he became a referee and used to oversee many of the County and England hockey matches.

My father was a Captain in the Royal Artillery Howitzer regiment and finished as a Captain. He was in action in France but as he never spoke of the war I have nothing to recount. Before joining he was with the Artist Rifles (subsequently 21 SAS).

He commuted to London from either Sutton or Cheam and took with him a flat 50 tin of Players which he finished each day. He completed The Times crossword daily during the journey to London.

Despite smoking he was pretty fit but in an accident he twisted his knee and had to have an operation to remove the cartilage. The surgery left adhesions and slowed him down but he still played excellent Tennis but could only referee at Hockey. He was excellent at Bridge and played for the South of England in many competitions. He was a member of a club in London where he played once or twice a week and the stakes were 2/6p a hundred a considerable sum in those days.

I adored my father he spent a great deal of his time with me we went to Olympia Circus, the Royal Tournament, Aldershot Tattoo and the Derby annually. He also followed greyhound racing, motorcycle dirt track racing and of course I spent hours watching hockey matches. They always had a party after the match and once being bored I made the mistake of saying "Daddy, that's your eighth whiskey". It put me off hockey though!!!

I must now come to my mother; a lovely lady almost permanently ill with a nurse in attendance. We now know that her whole body was affected by a blockage in her oesophagus which affected both her breathing and her digestive system; this results in food being blocked and a sick stomach occurring which involved endless major operations without curing the main problem. Today none of this would happen.

My childhood when on holiday from school was basically to keep quiet, look after myself and not to disturb mother. This does not really explain matters, however with my father being out most of the time and nurses and our servant Lloyd (my old nurse) to be avoided I lived very much on my own. By day I had friends around but come the evening I had to resort to my room and books. You do not want to be an only child.

I am far from proud over my behaviour towards my mother who was always most loving; sadly I did not return that love and by and large ignored her. Despite her illness she exerted a very strong influence over my father and me, all of it to our good. She died in 1952 aged 67 years in hospital after a major operation. As usual I have failed to do my mother justice. Perhaps I should mention that she was a devout Roman Catholic but this did not in any way affect her relationship with my father who was not of any particular calling. He adored my mother and did everything he could to make her happy but not surprisingly; he spent much time away from home.

I have left much out which I will have to rectify later but I suppose I must consider what I have to say about myself.

My first recollections are of 'Blackmoor' my grandfather's house and farm. When I was around 5 years I had, apparently, locked knees and fallen over whilst running. Medical advice was that I should wear leg irons and I was measured and fitted for these ghastly contraptions. My father with his knowledge of hockey injuries was far from happy and against medical advice took me to Blake a leading osteopath in London. I remember Blake sat me on his desk with my legs hanging down and said don't move and don't scream. He then manipulated my leg and knee joints and after a series of clicking sounds he said to my father. "He is OK send him to a farm where he can run around for 3 months and he will be fine." A great relief to me as irons on my legs would have been terrible.

At 'Blackmoor' I ran around with Sid Cox the farmer, was spoilt by his wife and had a wonderful 3 months.

The next thing I can clearly remember is going to St Anthony's Eastbourne at 7 years old. Probably because I was an only child and at home, mother being largely inoperative, I enjoyed school although we were fed badly and really suffered. Luckily my parents supplied me with a good tuck box but as the term progressed we were forced to resort to Moleys (that is bread spread with mustard, pepper and salt). Everything went well both academically and on the sports field until I caught double Pneumonia and Pleurisy. The situation became desperate and I was given the 'Last Rites' Extreme Unction.

My mother decided the school was no place for me and removed me wrapped in blankets with a temperature of 105 in our Austin 7 which she drove back to our house in Sutton at great speed where Dr Brown, our family doctor, was on hand. This was one time mother was not in bed and she certainly saved my life. However, the result of the Pneumonia and convalescence meant that I lost about two terms schooling. This was serious as although I passed the Common Entrance for Downside, the headmaster told my parents that I was not really up to the standard required by Downside and should go to Beaumont.

I left St Anthony's as Captain of the School, Captain of Boxing and Cricket and was Head Scout. The latter reminds me how different our attitude is to competition today. Our main sporting opponent in Eastbourne was 'Temple Grove' a school adjacent to our sports grounds. One year a joint Scout outing was arranged which took place on the South Downs. Both sides were issued with 3 white tapes attached to our scout belts and the object was to obtain as many as possible from the opponents and return to base. Little did the respective masters expect the battle that ensued; children were clutched together rolling down the hill and fighting tooth and nail scout staffs were freely used and much blood was spilt. We won!!! A memorable afternoon and great fun but we got severely punished.

Why, I do not know but it was a must for the more adventurous to leave ones dormitory at the dead of night and roam the school grounds and indeed the roof where I came upon the Maguire brothers cutting lead off the roof to make a cosh!! However the ultimate dare was to run to Beachy Head and collect something from the kiosk there and return unseen either by the school authorities or the Police. It was about a four mile run there and the problem was to get through the outskirts of Eastbourne without being spotted by the Police or any other busybody. My run went well enough although it was spooky on the Downs. I collected an ice cream sign from the kiosk and started the return journey wishing to God that I had never undertaken the run particularly as the moon became covered by clouds and there was a slight drizzle. I was dead scared and further aggravated by falling over a sheep half way home!! I made it with my trophy but what a stupid thing to do.

I look back with pleasure at my time at St Anthony's; we had some odd masters, Tip Toe Tibbet who bounced around the class room. Monsieur Talibart who always forgot to do up his flies and used to retire behind the blackboard to adjust himself but everyone could see him in any case. Harding used to bring his blood stained uniform to the class room when lecturing on the war. He had a dreadful temper and any boy who really irritated him he used to pick up and through out of the window. Robinson who smoked a frightful pipe would get fed up teaching a class and take everyone to the music room and play hot rhythm. Lastly there was Mrs Patton the Head Mistress, her husband, a lovely man was ineffectual like her son Anthony and daughter 'Ladybird'. However her husband was an inveterate gambler on horses which was largely the reason St Anthony's was so expensive.

The running of the school was left to Mrs Patton a real dragon and she did not like me; her favourite punishment was to seize ones hand and rap the knuckles hard with a heavy ruler. it hurt.

Summer holidays were mostly spent in the Isle of White or Cornwall; mostly Cornwall, based at Padstow where my Uncle Percy had a house. Lovely coves which were generally deserted and father spent hours with me fishing for moleys in the pools drawing lobster out of their holes with a long stick having a hook of steel at the end. We went spinning for mackerel in a fishing boat and shot cormorants from the boat. Knocked me down every time I fired the 12 bore but one got a shilling a head for cormorants.

This brings me to my school days at Beaumont. My first day was not a success; I was knocked down the stairs leading to the main gallery by some senior boys because I had my hands in my pocket. I then had to attend a choir audition and Clayton the Music Master did not believe I was tone deaf and unable to sing to the notes but thought I was taking the Mickey out of him and ordered me to beaten; 3 ferulas I think. I don't know why I have recorded this but it has always niggled me. However I much enjoyed Beaumont and ended up Captain of the School, Captain of Boxing, Captain of Cricket being both a wicket keeper and batsman and playing twice at Lords against the Oratory didn't do well. I was Captain of shooting and Under Officer in the OTC.

My academic progress was somewhat marred again by catching double pneumonia and pleurisy due to meandering back from a Rugger Match on Runnymede in the pouring rain and catching a chill. Once again I was at death's door and received yet again Extreme Unction; a Sacrament which I believe has now been done away with. A pity as I am sure it was this Sacrament and the prayers of the Beaumont boys that saved me as the school doctor was quite useless. My recovery was slow and I had a long convalescence which left me a couple of terms behind and which the Jesuits failed to re-arrange or encourage me to make up.

A few memories come to mind; my father who I suspect considered he had produced a moron was convinced that I could at least be trained in some game at which I could play for England. He deemed it was to be cricket and had me coached by some of the English team and spent hours hurling cricket balls at me and as I was made to stand with my back to a wall I became pretty efficient. However while I realised I was quite good at the game I knew I was not up to county standard let alone anything better. I became pretty depressed over the whole affair as above all I wanted to please my father and match him in playing for my country. Walking around the grounds at Beaumont with a Jesuit called Fr Tempest I broached the subject and he wisely said to me "you are good at most games and rather than be supreme at one you will have much more fun being good at a variety of sports". This was very comforting.

Remaining with cricket I recall that when wicket-keeping in a match a ball caught me in the mouth and knocked my two front teeth back into my mouth. Once again I recalled my father's words from his experience on the hockey field "if you get your teeth knocked out insist on seeing a dentist immediately and ten to one he will force them back and your teeth will be saved". I persuaded the master to take me to the school dentist and sure enough with the help of a gold band which I had to wear for several months the teeth survived and lasted for some 40 more years.

The most disastrous episode of my time at Beaumont came about due to my enthusiasm for .22 shooting for which I won 5 silver spoons to be seen in our silver cabinet. As captain of shooting I had access to the range at any time. We were allowed out of school onto Runnymede and the river front and used to explore the area past the 'Bells of Ouzeley' and even got a local publican to open up a back room where we could foregather and have a drink. Near this Pub was a large empty house which I thought it worthwhile to inspect. Having climbed the wall and obtained entry to the house I found a large hall which had three enormous chandeliers hanging from the tall vaulted ceiling. These had three layers of light bulbs and it occurred to me that they would provide excellent target practice.

Accordingly the following Sunday I removed one of the .303 Lee Enfield Rifles with a .22 barrel plus ammunition and repaired to the empty house where I proceeded to shoot out a number of the lights from an adjacent balcony. As this was great fun I enlisted a couple of friends to join me the following Sunday. Unfortunately the Police were lying in ambush; we split and bolted for any possible exit but I was hampered by the rifle and was cornered. The other two got clear away, one diving through the French windows.

From the Police Station I was eventually delivered back to the school. My father was summoned and agreed to pay compensation for the damage he was not pleased. I awaited my fate with some trepidation as I felt sure that I would be expelled. A couple of days later the whole school was assembled and the whole sorry business was disclosed in detail with much emphasis on stealing a gun and ammunition, vandalism, letting down the school etc etc. Finally I was given the choice of a birching or being expelled. I chose birching, a punishment which had never been used for untold years. The normal punishment was by ferula on the hand. Painful but bearable.

The birch was a two handed slightly whippy rod with a heart shaped gutt at one end with suction holes and ridges. This was delivered over my bare bottom and while I remember little about the beating as I passed out and regained consciousness in the sick room where I remained for some three days being patched up.

On surfacing I found that the boys were pleased that I had not given away the two other boys concerned and the Jesuits, who I am sure knew who they were, treated the whole matter as closed. They must have done as I became Captain of the School a year or so later.

I was sad to leave Beaumont and all my friends, unfortunately none of whom lived anywhere near me. Although it has its advantages it is far from easy being an only child.

Volume 2 Army life and preparation for the War.

While I had hopes to go into the Army my father was far from enthusiastic and had arranged for me to be articled as a potential Chartered Surveyor with Raymond Beaumont of 35 East Street Brighton. I reluctantly went along with his wishes and joined the firm having digs in a student's boarding house. I passed the Preliminary examination and was well into the Intermediate exam when I decided to quit. This was due to my social life and girl friends being centred around our home in Sutton and the work and digs were both boring an uncomfortable. My transport at this time was an AJ5 Motor Cycle which meant that my weekend trips were often both cold and wet whereas in Sutton I could borrow my father's car!!

The transport situation improved as my father gave me a second hand Wolseley Daytona an open 4-seater with a 6 cylinder engine. I got 90mph out of her Frankie managed 95mph. A great car but expensive to run to overcome this I sold her and with the money bought a brand new Standard 8 open 2-seater for stg120 super little car and economical but not the same class as the Wolseley.

I have failed to mention that during the Christmas holidays I twice went to Switzerland with my friend Poels and his family, once to Lenc and once to Arosa great fun but no ski lifts, we used to climb for 4 hours with skins on our skis very exhausting for a 20 minute run down. I also went twice to Lourdes as a stretcher-bearer via a train filled with the sick and disabled. A very interesting time and despite the commercialism one could cut the faith in the atmosphere with a knife. A hundred thousand Christians marching with lighted candles up the steps past 3 churches to the summit was an unforgettable sight.

Back to quitting being a Chartered Surveyor. My father was furious but resigned and he and a number of friends arranged for me to be interviewed for a variety of jobs. This resulted in my making a major mistake. I had two interviews in one day, one with Shell at which I was offered and accepted a job with PLUs and unlimited prospects with good money and a life time career. That same afternoon I went for an interview with Thomas Cook. As the interview progressed it was clear that if accepted I would get a better salary and special management training in a section they had recently set up. This included trips abroad, attachment to the Indian Section, cruises, courier experience and free travel abroad.

Stupidly I cancelled the opportunity with Shell, which created much furore and took the job with Thomas Cook.

I went on a training course, visited both Holland and Belgium and arranged for the various comforts, some unusual, of several Princes and their entourage from the Indian section. Later I also went as Assistant Cruise Manager twice on the Orion and once on the Oriana. These cruises were great fun, two weeks in a first class cabin and I had to wear evening dress every night. The Manager and I ran a small office on board and were responsible for all the travel arrangements on each visit to the various ports of call; that is transport, dinners, night clubs, casinos, excursions etc. Most comfortable and interesting were these cruises, First Class only and we as Cruise Officers were treated as such and also had an allotted table with passengers in the dining room and a luxurious cabin.

There were two winter cruises; one covered the Norwegian Fjords and called at Oslo, Bergen, Molse and Trondheim and then onto the Northern Lights. The other was a Scandinavian tour calling at Danzig, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Helsinki, Goteborg and Oslo.

Early in 1939 I was proposed by my cousin Jack Jones and seconded by Eric Biseley for the Honourable Artillery Company and was accepted by the Court of Assistants. This is the oldest Regiment in the British Army raised in 1537 by Henry VIII and was one of four territorial officer producing units, they were the best club in London and very difficult to get into. The HQ is at Armoury House, Finsbury Square in the City. The other three Regiments were The 'Artists Rifles' in which my father was a member, The 'Westminster Dragoons' and The 'Inns of Court' a Cavalry Regiment.

The HAC had two artillery regiments and an infantry battalion, I joined the latter. Discipline was very strict and the highest standard of dress and maintenance of weapons and equipment was insisted upon. However once above the ground floor of Armoury House there were no ranks and Christian names were used.

I much enjoyed the training and social activities and the summer camp at Warminster with the other three officer producing units. Custom allowed us a wine tent in the field, so we had on our tent lines an enormous marquee in which wine etc was served by stewards and waitresses, much to the envy of the other units. War was clearly nigh so the training both physical and military was hard and we both played and trained with zest. As a matter of interest there must have been over 2000 cars in the car park. Rich.

Prior to all this I had the good fortune to meet Frankie. I was invited to a party at Col. Burton's house in Woolwich. He was killed on a hospital ship bombed by Japs leaving Singapore as Chief Medical Officer. Peter Burton his son a great friend of mine from Beaumont was the instigator of the invitation and in those days you did not take a girl friend but were introduced to one of the opposite sex who was nominated your partner. I got Frankie - a stunning girl I was well pleased and very lucky. We had great fun and that was the start of my courtship.

It was, I think, on the 3rd September that war was declared and I reported to the HAC where the regiments were mobilising. I recall an air raid warning sounding a false alarm I think. However, orders were given to dig-in and we proceeded to ruin the immaculate cricket, rugby and hockey fields belonging to Armoury House by digging a First World War trench system.

In a couple of days we formed up and marched through London with bayonets fixed, drums playing and colours flying as was our right. Few people took any notice!!!

We entrained and landed up at Bulford where we started 162 OCTU (Officer Corps Training Unit). As officer cadets we had to undergo further training before we were commissioned. At this stage we lost about 80 cadets who either had their own planes or a pilot's license and rightly they went to the RAF.

We marched, dug, shot and familiarised ourselves with a variety of infantry weapons; grenades, light machine guns and mortars. We drove a variety of army vehicles and motor cycles. I had a break here as a number of new motor cycles had to be collected. Volunteers were asked for and while all could drive cars only six of us could handle motor cycles with any degree of expertise. For a couple of days we were driven out to a collecting point and took over brand new Nortons. We had great races back to camp.

I was, with many others, commissioned on 15th December 1939. This ceremony was somewhat marred by the new Commandant failing to understand the somewhat lively exuberance that was customary amongst members of the HAC when celebrating. Admittedly we had overdone it the previous night and few could have slept. The Commandants house had been singled out for some spectacular decoration.

The upshot was a full scale parade, a vitriolic lecture and all cadets commissioned were ordered to dress in fatigues and report to the drill square. There we were given full packs loaded with rocks and told to double round the square for 20 minutes anyone falling out would loose their commission. Round and round we went with Warrant Officers stationed at every corner. Fit as we were we all had major hangovers and the rocks bounced and cut into our backs. However, with mutual help we all made it; two hours later we left camp in our cars with all horns blazing and with the cheers of the remaining members of the HAC. The Commandant was not pleased.

After a couple of weeks leave at home and visits to London where I got myself kitted out with uniforms; Mess kit, Blues etc by Conway Williams our regimental tailor and endless parties with Frankie, I left in my little open Standard 8 to join my regimental depot at Sobraon Barracks, Lincoln.

I reported to the depot on 29th December 1939 late afternoon in a snow storm and on arrival at the "keep" my car broke down at the Guard Room where I had reported. I found out the location of the Officer's Mess and told the Guard Commander to have the Guard push my car to the Officer's Mess. A bad move.. as the following day I was up before the Commanding Officer and told in no uncertain term that I had broken practically every rule in Military Regulations and would if it were not for the war and being just commissioned been court martialled.

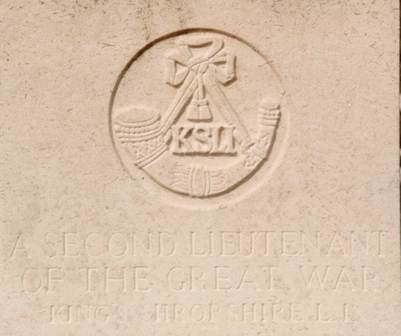

Life at the depot was comfortable with much social life. A number of our subalterns were awaiting postings to one of our battalions there was one in India and one in France. Training continued daily but we badly wanted a platoon of our own to command. I had done well with both the HAC and at 162 OCTU and wondered why I had not been commissioned into the Buffs or Queens, both Regiments I had asked to join. I had hardly been north of the Thames and had to look at a map to find Lincoln!! Notwithstanding other officers at the Depot were also mystified over their own posting. It appeared that the eight warrant officer platoon commanders in each battalion were to be withdrawn as with their many years experience they were not expendable whereas 2nd Lieutenants were. Hence the random postings.

One light relief was that Bertie Burridge, a brother officer from the HAC, and myself were detailed to take a mixed draft from a number of infantry regiments to Rouen base depot from whence they would be despatched to their various regiments. All went well until we arrived at Le Havre where I was told there would be a five hour delay before we could entrain for Rouen. Bertie and I decided it was unreasonable to keep the two hundred men sitting around the platform, so having seen to a guard being posted on the kit and arms gave permission for the remainder to visit Le Havre town and report back in four hours. How stupid can one be As the first drunks appeared about four hours later, the message got through!! We got hold of some Military Policemen with jeeps, got the train delayed and scoured the bars and brothels of Le Havre. When we left we were still missing six men who were subsequently found and sent on. The C.O. of the base depot was not amused and told us to report to our battalion in France and not return to the UK. Luckily I had a letter from the C.O. of my depot saying that on delivery of the draft we were to report back to our own depot in Lincoln. We spent an uncomfortable night in a bell tent with ice on the ground and only one blanket but as we had managed to spend that night out on the town we felt little pain. Then back to Sobraon Barracks until 6th April 1940 when eight of us were posted to the 2nd Royal Lincolns and were stationed at Ronchin a few miles south east of Lille.

The village was small and poor with few facilities. The officer's mess was located in the Mayors office and was just adequate. I was billeted in a local house tiny room with no bath and an outside loo. My platoon in 'C' Company under Major Charles Boxer a splendid man was entirely made up of long term experienced regular soldiers. I am pretty sure they looked upon me as an absolute twerp. My platoon sergeant tactfully suggested he handle the platoon until I was well settled in. This I wisely accepted and during exercises and our continual digging of the extension of the Maginot Line in the way of massive tank traps I had no problems. They came to accept me and I knew I would be able to lead when the war started.

Life in the Mess was boring; subalterns were not allowed to leave the table while any field officer was still seated. As the Company Commander sat drinking port for hours on end this rule was particularly galling. However Mess nights only occurred three nights a week and on other nights we could visit Lille which was full of life and catered for the British Army which was in the vicinity.

Our battle plans involved a swift move to Louvain once the Germans attacked the Maginot Line. Unfortunately the Belgians would not let the British or their allies carry out a reconnaissance in uniform which meant that Company and Battalion Commanders had to sirreptitiousely visit their planned battle positions in civilian clothes and in civilian cars. All very tiresome and stupid but it was done.

We had everything prepared for the advance and knew exactly who went were and what was loaded in every vehicle including troop carrying vehicles which were permanently on stand by. When finally on the 10th May at the Officers Parade Eric Hefford the Adjutant received a signal and on reading it said "Gentlemen the war has started Activate Plan 'D'".

Volume 3 The War (Dunkirk)

I rushed off to my platoon and found that my batman Sutton had all my fighting kit packed and loaded and the rest had been left with the Rear HQ. The platoons were ready and my platoon sergeant reported to me "Sir, you will now lead the platoon and I will cover the rear." I said "fine sergeant but why are you at the rear?" "To shoot any bugger who runs" he said!!

Our move to Louvain (Leuven) was straight forward and without incident. We settled into our predetermined positions dug in and awaited the Germans. My platoon was the left flank unit of 'C' Company and the battalion. I was told to liaise with the Belgians on my left; this I did to find a highly excitable major in full dress uniform and sword shouting at, even to my limited experience, a thoroughly ill-disciplined and disorganised unit. I reported to my Company Commander, Charles Boxer and he told me to keep a close eye on this left flank. My corporal commanding my left flank section reported at 0400hrs that there was a lot of movement in the Belgium lines. I went over a little later to find that the whole Belgium unit had left and our whole flank was wide open. My Company commander moved us further left but we could not cover the gap and it later became clear that the whole Belgium army had capitulated without a shot being fired.

We came under mortar fire on 11th May and direct contact was made later in the day. We were well dug in with good fields of fire and were looking forward to an enemy attack. In the meantime 'the powers that be' decided that our forces were being spied on by Belgian defectors and that Louvain (Leuven) must be patrolled by units to flush out any spies or wireless transmitters five transmitters were found but unmanned. The only patrol I went on was a disaster; I took an NCO and three men and covered a number of specific buildings without any sign of occupation, Louvain had been evacuated.

On my way back to my platoon I realised I had left my gas mask in one of the buildings so I told my small party to return to base while I went back alone to the building. Just as I reached the house I thought I saw a flicker of a torch light upstairs what to do? I had to have my gas mask so I decided to go ahead. Drawing my revolver I went into the house and moved slowly upstairs where my gas mask had been left. Leaping into the room there was nothing however on picking up my gas mask I felt something was wrong and decided to leave by the back stairs. I was quite definitely frightened and had my revolver ready. Reaching the back door with relief I opened it and the moon shone sufficiently to show the way when out of the semi darkness came an Alsatian which was clearly trained to attack, I fired all six shots into the beast and ran for it. Hence my dislike of this breed.

The next day my platoon came under mortar fire and the enemy probed the strengths of our positions. They attacked the following morning and were repulsed although we suffered a couple of casualties. My platoon sergeant presented me with a P & P Luger probably taken from a warrant officer we had killed in the action. Kept it all the war until 1960 when it was stolen from my car in Turkey. A pity, it was 12mm and the only hand gun I was ever accurate with and served me well in Palestine.

For no apparent reason we were told to withdraw. This happened time and time again with no explanation and to us no reason. We never lost contact with the enemy and never lost a battle. We often counter attacked to regain a position and to consolidate, we suffered casualties but were never beaten. We retired along roads filled with refugees - vehicles - carts - prams - women - children fleeing from the relentless bombing and strafing by German Stuka fighters which came screaming down (and I mean screaming, they had sirens activated by wind speed when they dived), machine gunning and bombing the mass of civilians and army indiscriminately . We eventually learnt to stand and shoot with rifles and Bren guns as they straightened out at 300-400 feet and where vulnerable.

As the retreat continued our losses mounted, Tony Newbury our C.O. was killed and Geoffrey Lawe the 2 i/c took over Eric Hefford our adjutant was hit and Tony Noble took over. Charles Boxer my Company Commander was hit in the backside during an attack but insisted on the splinters being extracted before we continued the battle and won. However I had lost, either killed or wounded over half my platoon and it was decided to reduce 'C' Company to two platoons instead of the normal three. Darby Hart took over the rest of my platoon and I was made Intelligence Officer.

This meant that I joined battalion HQ and had a small intelligence section with a sergeant and five men plus two motor cycles. The latter were bliss; I and my sergeant were mobile and could recce both forward of our own battalion and as time went by the routes through which we were ordered to withdraw. I had a good liaison with Peter Rowell who commanded the carrier (light tracked vehicles) platoon and we blew up a couple of bridges. On one occasion we waited until the leading German motor cyclist with a side car was crossing and then blew it. Very satisfactory we left in a hurry and as I leapt on my motor cycle I hoped to God it would start!

Alistair Fennel, one of our officers at brigade HQ used to arrive day after day and tell us that we had to retreat no explanation it was difficult because our men were seasoned soldiers and had proven to be better fighters than the Germans. Yet back and back we went through an endless mass of refugees and harassed by Stuka fighters. All bad for morale yet the battalion was in good fettle. Confidence, God knows why, was high and we felt capable of competing with anything that the Germans could throw at us. By this time Gerald Tatchell had been killed and Tony Cartland (Barbara Cartland's brother), Bertie Burridge my friend and ex HAC officer was killed and also Burrell. Goulson had been hit and Gough too and our overall strength only amounted to around four hundred.

While all this was going on, I had little time to think of Frankie being either too exhausted or immersed in the many problems involving my intelligence section; furthermore as I was attached to the battalion HQ I was aware of all the command decisions and orders. Notwithstanding I had Frankie on my mind as she had volunteered before the war as an ambulance driver with the London County Council. Rumour had it that London was under threat and had been bombed and I rightly assumed that as she lived with her parents in Beckenham she would be on duty covering London. This was in fact so and driving a heavy vehicle in a blitz or just covering accidents or fires was no place for a young girl. However there was nothing I could do.

On leaving Louvain (Leuven) the battalion had passed through Brussels over the River Dendre and the River Dyle to a defensive position on the River Escaut. Rations were non-existent and the battalion lived off the land and foraged for eggs, pigs, chickens, sheep and cows. Then on the move again through to Tourcoing and Zuydschoote where the battalion came under heavy attack on 29th May; it is said that the 8th and 9th Brigades (we were in the 9th with the 1st Kings Own Scottish Borderers and 2nd Royal Ulster Rifles) held up the German Army Corps for a day thus helping the evacuation from Dunkirk of some many thousands of the B.E.F. (British Expeditionary Force).

On this day I was ordered to recce routes to Dunkirk for although 3 Division were told to cover the withdrawal and fight to the last man the C.O. thought it worthwhile to check out the route and have the intelligence section study the ground from a defensive point of view.

I remember sitting on a wall viewing Dunkirk mole and the beaches with my section. It was a shambles Dunkirk was on fire with shells landing on the mole and the vicinity every few minutes. The sky was full of stukas which together with the German artillery were bombing, machine gunning and shelling the beaches. Queues of soldiers were forming up behind make-shift moles of 3 tonners driven into the sea with wooden slats over the roofs for boarding purposes. Whalers and small craft came in and waited chest deep for men to clamber aboard; there were many casualties and I thought the whole affair very dangerous indeed.

We returned to the battalion to find the remnants en route to Furnes near Veurne, East of Dunkirk. Here we were told that we would cover the withdrawal to the very end. We re-organised into two companies and an HQ company having about 45 men including my intelligence section which by sheer luck was still complete. Small attacks by Germans occurred but nothing serious. Waves of bombers went over to lay waste the Dunkirk beaches and we were shelled throughout the night.

Early 31st May we were told to withdraw to La Panne. That evening the remnants of the battalion left for the beaches; on arrival it was dark except for the many fires and sporadic shelling. The battalion was directed to the Bray-Dunes and formed up with 50 men to a guide provided by my intelligence section and marched some four miles to a jetty made up of sunken lorries and duck boards on top. The tide was out and no one could get to the boats so we marched another nine miles to Dunkirk. Finally the shelling, the casualties and the exhaustion caused the C.O., Geoffrey Lawe to call the officers together all eight of us - we were to split up with some 25 men each with orders to do our best to get back to the UK.

As Dunkirk had proper berthing facilities albeit under fire I led my party to Dunkirk. We boarded a Destroyer which unfortunately was both bombed and shelled as it left the mole. I and many others bailed out.

Gathering men from various regiments including Worthington, the Commanding Officer's batman I moved down the beach towards the Bray-Dunes; the tide was coming in and whalers and small craft were coming within wading distance so we scrambled aboard where we could. I found myself on an old wood burning small steamer commanded by a naval Lieutenant who obviously hadn't slept for days and could hardly move from the bridge. He called out to me (mistakenly I had assumed that as I was in the hands of the Navy all was well and we had no further problems) to have all the weapons loaded (brens and rifles) and all able bodied soldiers to man the decks as we would likely be attacked en route. The remainder to care for the many wounded.

How right he was, we were attacked seriously three times but with some 20 bren guns firing we discouraged the enemy saw no RAF.

We arrived at Dover late on 1st/2nd June and embarked in the nearest train and woke up in Camberley. I contacted the parents and then Frankie to whom I suggested that as life as a subaltern was precarious, what about getting married. She agreed. I then slept for 24 hours.

We got married at St Edmunds in Beckenham on 11th June 1940 in a great rush; unfortunately Frankie was denied a full scale white wedding. The 2nd Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment was to reform at Castle Cary in Somerset and after a 48 hour honeymoon that is where we went.

The End.

GISS - GOSS

GISS GOSS is THE REVIEW gossip column with tittle-tattle gleaned from various sources.

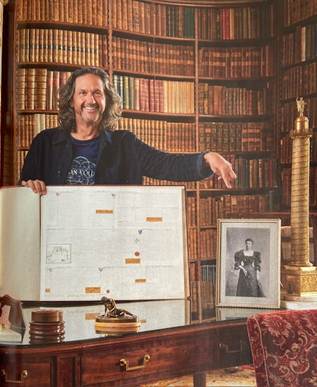

From Country Life:-

This Magazine has produced a couple of articles relevant to Beaumont. The first concerns The Tempest family: The connection her goes back to Sir Charles Tempest:-

Born on 5 January 1834, he was the son of Henry Tempest of Heaton and his wife Jemima, second daughter of Sir Thomas Joseph Trafford, 1st Baronet of Trafford Park, Manchester. He married, firstly, on 21 May 1862 Cecilia Elizabeth Tichborne, daughter of John H. Washington Hibbert of Bilton Grange. In 1866 he was created 1st Baronet Tempest of Heaton. His first wife met her end by a terrible accident when her dress caught fire and she burnt to death. 'Sir Charles, who was severely injured in endeavouring to extinguish the flames, experienced a great shock by his wife's lamentable death, and from that period until his second marriage he lived the life of a recluse'. Despite this he sent his son and heir Henry to Beaumont which he left in 1875. The year before Sir Charles met and fell in love with Harriet Manson Gordon, a seventeen-year-old girl of good family, and the two were married on 1 June 1874 at the Bavarian Chapel on Warwick Street. In 1877, however, his young wife eloped to Paris with an acquaintance of her husband's, Henry Vane Forester Holdich Hungerford. For three weeks the two lovers lived together under the name Hungerford at the Hotel Wagram in Paris, before embarking from Le Havre for the United States; however, Lady Tempest soon returned alone. Sir Charles Henry Tempest divorced her in 1878. He died on 1 August 1894, aged 60. Sadly, Henry predeceased him in 1891 and the Baronetcy became extinct. The family fortune went with Sir Charles' daughter Edith to save Carlton Towers for the Fitzalan Howard Family. Roger below is descended through Sir Charles's younger brother.

The next articles concerns the re-building of the House of Commons after it was partially destroyed in WW2 and the artchitects appointed were Sir Giles and his brother Adrian Gilbert Scott.

THE CUTLERS

A son and his father that trod very different paths.

Horace G. 'Hank' Cutler, Ph.D., a celebrated natural products chemist whose career spanned more than half a century, died June 1, 2011 in Watkinsville, GA at age 78, after suffering from cancer. He was born in London, England, on November 21, 1932, to Sir Horace Walter Cutler, O.B.E., K.C. and Betty Martin Cutler. He grew up in London during WW II and had many memories of the blitz. Dr. Cutler attended Beaumont College Jesuit boarding school in Old Windsor, Trinity College, Dublin, Columbia University, New York and the University of Maryland, College Park. At the age of 20 he immigrated to Quebec City, Canada, and then moved to New York City. In 1954 he accepted a Union Carbide Fellowship with Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research in New York. It was during a Good Friday Mass that he met Joanne Steinmetz, who also worked at Boyce Thompson. They were married in 1955. During his Fellowship he realized his passion for natural products research while working with Lawrence "Larry" King on plant growth regulators.

This passion drove him to embark on a 57 year career in natural products research. While working with Dr. King, he was involved with the development of the insecticidal agents possessing carbamates, which eventually lead to the discovery of carbaryl (Sevin(r)) by Union Carbide. In 1959 he accepted a position as a Plant Physiologist with Tate and Lyle, Ltd., Central Agricultural Research Station, Carapichaima, Trinidad, West Indies. While in Trinidad he was able to work with a team of researchers that investigated a wide-swath of plants for bioactive compounds. Among other developments, this work eventually led to the development by Tate and Lyle of the sweetener sucralose that and is currently sold in the US under the trade name Splenda(r). In 1963 he enrolled in the University of Maryland to earn a Master's of Science (1963-66) and Doctor of Philosophy (1966-67) degrees in natural products chemistry. Upon graduating from the University of Maryland he was appointed Plant Physiologist with the United States Department of Agriculture - Agriculture Research Service in Tifton, GA, to develop a modest natural products program within the USDA. It was during that time that he became interested in evaluating the secondary metabolites of plants, fungi, and aquatic organisms for their biological effects. In 1981 the USDA interests in the natural products program had grown to the point where they asked him to relocate his research group to the Richard B. Russell Centre in Athens, GA. This afforded him the opportunity to become more engaged with his adjunct professorship at the University of Georgia and support graduate students of various departmental programs within the university system. In the late 1980s he served on a USDA-ARS Special Committee to secure federal funding to build the Phase I of the National Centre for Natural Products Research in Oxford, MS. His research group relocated to this site in 1995 when construction of the Centre was completed. It was at that time that Hank retired from the USDA as a GS-15 Research Leader and volunteered his time at Mercer University College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences as a Senior Research Professor. This faculty appointment gave him the opportunity to educate pharmacy students and to direct graduate students working on PhD degrees in pharmacy research. He also held an adjunct professorship at the University of Mississippi School of Pharmacy. During his 57 year career with the USDA and Mercer University, Dr. Cutler was recognized nationally and internationally for research on the isolation of biologically active natural products from fungi and plants. He published over 200 peer-reviewed papers, 33 book chapters, 13 books, over 150 national and international scientific presentations, and more than 50 US and international patents.

He served as Fellow of the American Chemical Society, was awarded the Silver Medal for Research from the Japanese Society for the Chemical Regulation of Plants, the Plaque of Appreciation for Contributions to Science by the Korean Agricultural Chemical Society, and the Abbott Pharmaceutical Award. He served as President of the Plant Growth Regulator Society of America (PGRSA) and as its Chief Executive Officer. He was a member of the honor societies Sigma Xi, Rho Chi, Phi Lambda Sigma, and Phi Sigma as well as a member of the New York Academy of Sciences, the Georgia Academy of Sciences, and the American Chemical Society. In 1989 he was selected by the American Chemical Society as the state of Georgia Chemist of the Year. The USDA-ARS recognized him in 1990 by awarding him the Outstanding Award for Performance. He was a member of the University of Georgia Catholic Center where he was a professed Secular Franciscan. For more than 40 years, he was a lector at various Catholic Churches and served as a Eucharistic Minister for much of this time. He is buried at the Honey Creek Woodlands of the Monastery of the Holy Spirit in Conyers, GA. He is survived by his beloved wife of 56 years, Joanne Cutler, seven children (spouses), Frank Cutler, Paul (Debra) Cutler, Chris (Karen) Cutler, Kevin Cutler, Stephen (Jill) Cutler, Elizabeth "Liz" (David) Grow, and Holly (Keith) Kendrick. He also leaves behind 12 grandchildren.

The Father Sir Horace Cutler

Horace Cutler was the most formidable figure in the politics of London since Herbert Morrison, the pre-war leader of the old London County Council. But whereas Morrison went on to perform on the national stage - becoming Home Secretary and Foreign Secretary, as well as Deputy Leader of the Labour Party - Cutler's achievements were confined entirely to local affairs.

He did, however, make two stabs at a parliamentary career. In 1960 he had high hopes of securing the Conservative nomination for Harrow West, Harrow being his native turf; but he lost out to Jack Page. In the 1970 General Election he fought the Labour seat of Willesden East: he lost, and thereafter forswore national politics, devoting his abundant energy and acute mind instead to the affairs of London under the aegis of the local government behemoth which was the Greater London Council, of which he was Leader from 1977 to 1981.